“Boots on the Ground” is a 2017 film written and directed by Louis Melville. The story centers on a group of British soldiers torn apart by greed and demonic forces as they try to survive the last night of the Afghan War.

Found footage fans should already be familiar with Melville’s work, as he served as a producer on the 2003 feature, The Last Horror Movie ( 2003). Released on DVD as a part of Fangoria’s Gore Zone imprint, The Last Horror Movie ( 2003) has grown to be something of a cult classic over time. Boots on the Ground marks Melville’s second feature as director after The Man Who Sold the World (2006).

Boots on the Ground follows a group of five British troops on the last night of the war, introducing the characters as they’re retreating from a firefight. The small platoon makes their way to an abandoned fortress after seeing a group of what appears to be another group of British soldiers disappear inside.

Once locked in, troops uncover one hundred million in American dollars in a hidden room. As the night progresses, the platoon is torn apart not just by paranoia over the money and who might want it for themselves, but also by the mysterious, otherworldy forces that have taken root within the fortress.

These hardened soldiers truly believe that they are ready to deal with any threat that comes their way, but their training and fortitude are put to the test as they come face-to-face with demonic forces they could never have prepared for.

Found Footage Cinematography

The cinematography in Boots on the Ground is strong, for the most part. Each character wears a helmet-mounted video camera. This cinematic approach offers authenticity to the footage akin to actual head-mounted cameras sometimes used by the military. Since each character is armed with a video camera that is always recording, director Louis Melville has the luxury of using these multiple POVs to compose scenes that look more like traditional narrative filmmaking, while maintaining the film’s found footage conceit.

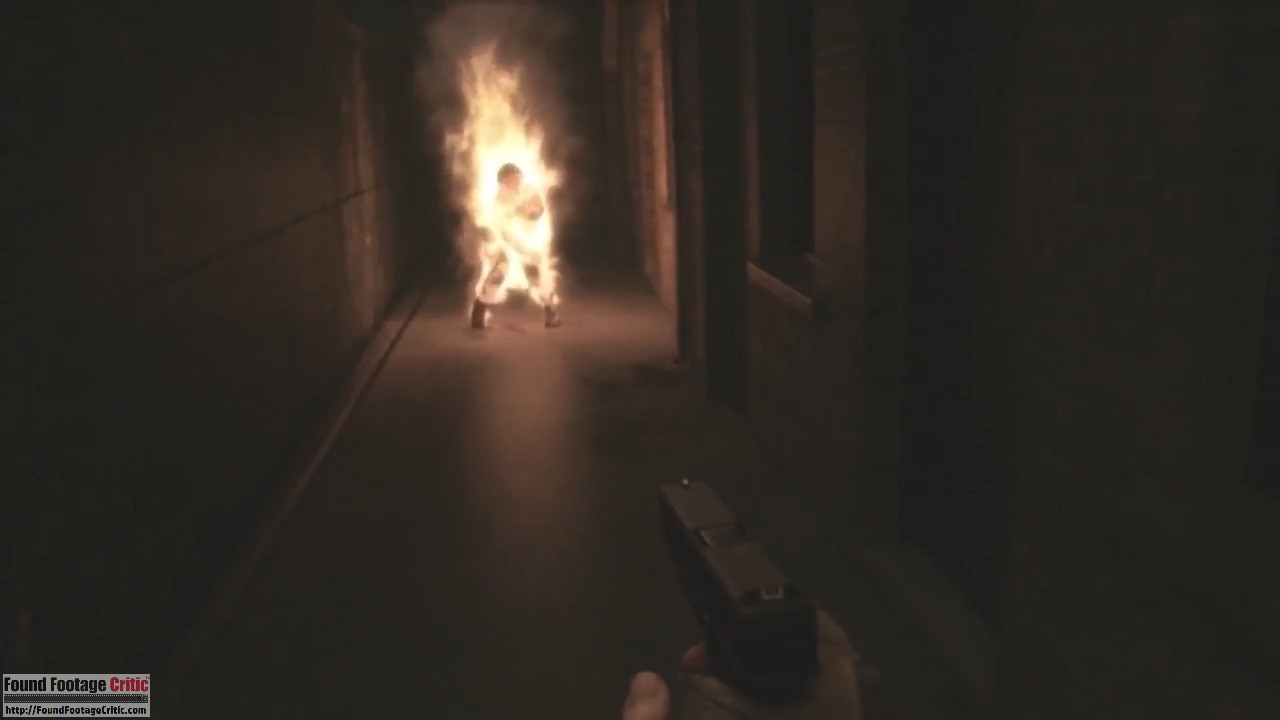

In many ways, because of the way the film is shot, Boots on the Ground also looks and feels at times very much like a first-person shooter video game, such as Call of Duty. But Melville seems acutely aware of this comparison and subverts it in smart ways. Boots on the Ground doesn’t simply feel like a first-person shooter adapted for live action, as was the case with Hardcore Henry (2015). The action sequences that typically define a video game of this style aren’t as crucial in Bootis on the Ground. When the characters are firing, Melville never makes it quite clear who or what they’re firing at, and there are a few times when the soldiers are clearly shooting at something that isn’t even there.

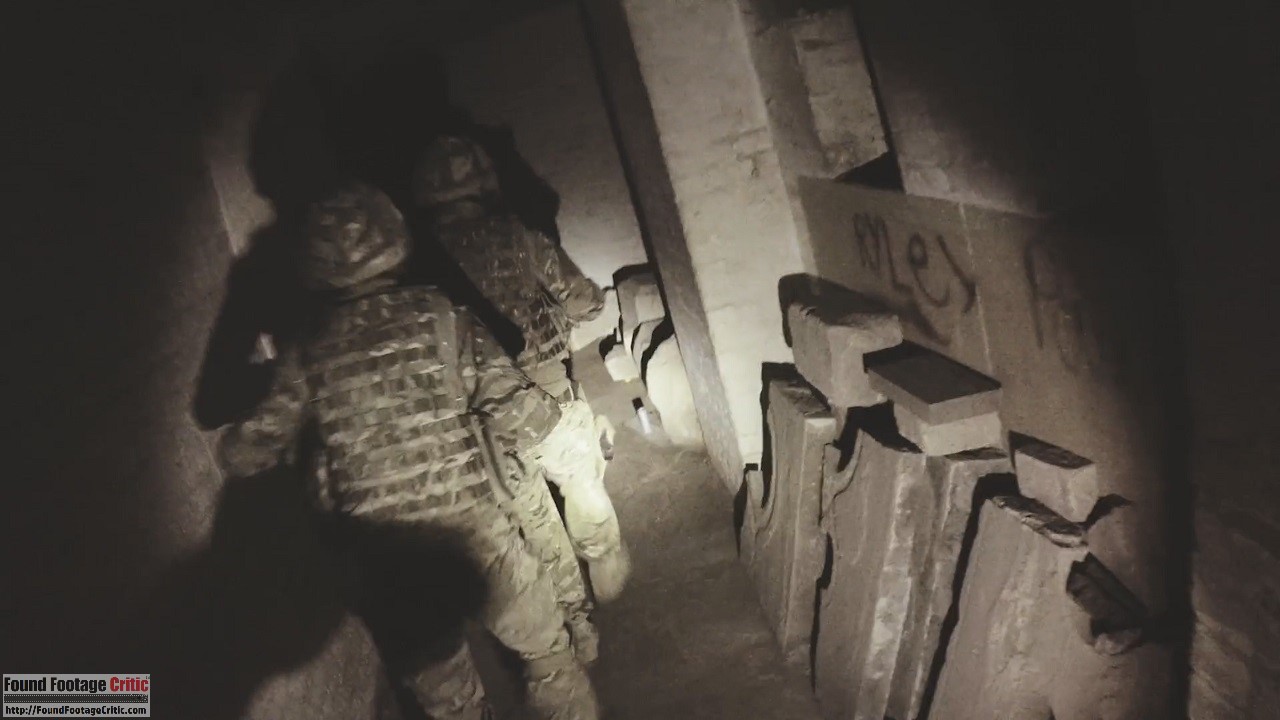

The shocks and scares in Boots on the Ground don’t come during the action moments, but rather during the lulls when the characters take a moment to breathe. That’s not to say that the film doesn’t feel incredibly tense at times, either. As the characters explore darkened hallways and jump at every shadow, the story makes it next to impossible to predict exactly when a scare might come. This approach is likely to bring down the guard of unsuspecting viewers just before something frightening actually happens.

One challenge faced by Boots on the Ground takes place during scenes where the characters explore the darkened, creepy hallways of the cavernous fortress. During these moments, the solider’s flashlights often consistently blink on and off. This technique works well the first time it’s used and makes for an effective scare. But the more it’s used, the more the technique loses its impact. Unfortunately, some viewers may find the persistent flashing grating and difficult to watch.

Visually, Boots on the Ground does skirt around feeling like a first-person shooter video game walkthrough, and while this approach certainly works at times, the often chaotic and fleeting POVs can become incredibly difficult to follow during moments of extreme action when rapidly cutting between the different video cameras. These characters are trapped in pitch-black darkness and are all wearing the same uniform, which may make it difficult for some viewers to track the characters.

Since the characters are presumably armed with military grade video cameras, the footage would have come across as more authentic had each camera included a time stamp and character’s name. Not only would this have added realism to Boots on the Ground, it would also have made that story much easier to follow.

As is evident in the trailer (for those who haven’t yet seen the film), Boots on the Ground utilizes quite a bit of CGI. With a found footage film in particular, unless the CGI is convincingly real, it is likely to take viewers out of the moment. Unfortunately, this is the case with some of the CGI in Boots on the Ground. In retrospect, we feel the film had an opportunity to use practical effects or other workarounds to avoid using front-and-center CGI. As a final note, the periodic camera glitching used throughout the film adds to the overall authenticity of the footage.

Despite the technical challenges described in this section, director Louis Melville does a good job creating a unique atmosphere and feel to Boots on the Ground that clearly distinguishes the films from other like-minded films in the found footage genre.

Filming Reason

Boots on the Ground is shot entirely by the characters via helmet-mounted video cameras that are always recording. The military (at least in the United States) is known to arm soldiers with video cameras to capture a visual record from a mission. At one point or another, many of us have seen news reports or documentaries of military footage in the same vein as the visuals in Boots on the Ground. The military will often use similar video cameras to obtain proof of a confirmed kill of a high-value target. Quite often such footage is recorded to analyze soldier performance during training exercises.

While the events of Boots on the Ground are clearly not a training exercise, the use of POV cameras on each of the characters makes sense and offers plausible deniability as to why the video cameras are always recording. The film presumes that their video cameras are standard issue, which is bolstered by the characters wearing the cameras never verbally addressing them. In fact, the only attention that’s ever drawn to the video cameras is a single moment when the characters review footage from the cameras to try and get a sense of where their comrades are after being split up.

On a technical level, the filming reason is almost seamless, successfully enabling viewers to almost forget about the video cameras. Since the characters wear the video cameras on their heads and they record automatically with no human intervention, the cameras are an organic part of the story. Since the cameras record everything automatically and recording everything is presumably a military mandate as part of their mission, the found footage trope of a character saying “Why are you still filming this?” never comes up. The hands-free video recording also lends to the plausibility of the characters continuing to film while faced with grave danger, a facet of found footage films that often falls by the wayside. Boots on the Ground effectively skirts this issue.

Found Footage Purity

The found footage purity examines how well a film comes across as “real” found footage. This section takes into account the acting, cinematography, special effects, and story. For the most part, Melville believably sells Boots on the Ground as true combat footage, but the film is faced with some challenges.

The acting and characters are definitely believable enough to sell the story. The performances are unlikely to take viewers out of the moment or remind them that they’re watching something manufactured. Even if the characters take no time at all to start jumping at each other’s throats, their reactions make sense because of how high the tensions already are at the moment they are first introduced. The distrust, greed, respect and lack thereof between characters all feel genuine.

Perhaps, the biggest issues impacting the found footage conceit is in the film’s structure as more of a traditional narrative film rather than found footage. Boots on the Ground includes a hook at the film’s opening that is actually a moment taken from much later in the story, which is an editing technique often used by narrative features that would not make any sense if this were actually raw footage unearthed sometime after the events take place.

Nonetheless, this approach makes sense considering that this footage is clearly edited by a third party and isn’t meant to be presented as raw. But even then, one has to wonder why such footage would clearly be edited as a horror film if it was meant to be presented as evidence in a case. This is where the inclusion of elements like the cold open and the music don’t really gel with what the film is trying to present. It’s also questionable that these characters would even be discussing some of the things they talk about, like killing each other for the money, if they knew they were being recorded. Without giving away spoilers, even the very notion that the film is edited by a third party doesn’t make much sense when everything is revealed by the end.

The film includes wall-to-wall non-diegetic music, including several musical stings building up to some of the film’s larger scares. Each and every one of them is likely to take viewers out of the picture to remind them that they’re watching a movie and not something that actually happened.

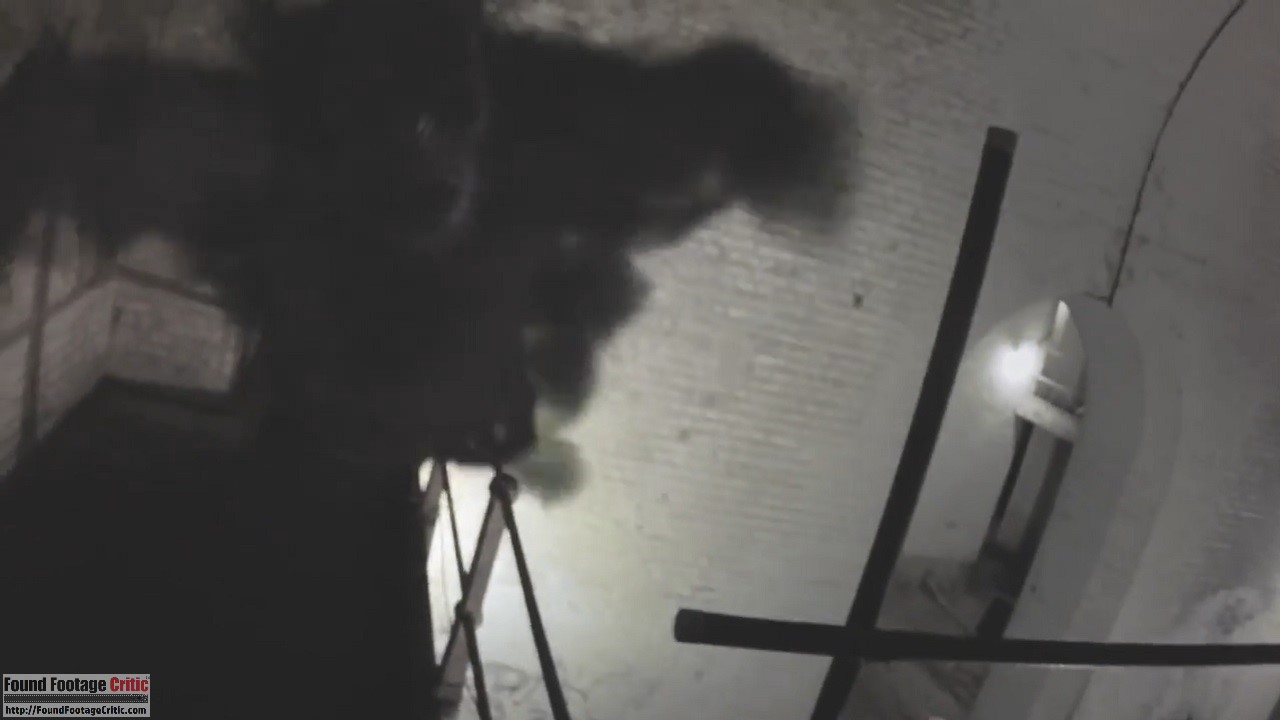

Unfortunately, the computer-generated visual effects detract quite a bit from the overall found footage conceit of the film. There are truly fantastic moments of the characters simply creeping around in the dark, and those moments are genuinely scary. There are times when they might jump at so many shadows that you let your guard down, almost convinced the scare might not come—and then it does. When it’s a glimpse of a practical creature, it’s fine. It works for the moment. But when it’s a billowing dark cloud of smoke, as it winds up being most of the time, it doesn’t work at all. The film includes a scene where a character is on fire and it’s supposed to be both horrific and emotional, but the quality CGI doesn’t come across as either.

The shame in that is that those CGI moments don’t feel like they couldn’t have been avoided, they don’t feel necessary, and every practical sequence looks so much better, so it’s hard not to think that the film would only have been stronger had those VFX shots not been included. Despite these challenges, Boots on the Ground does a decent job at selling itself as actual found footage.

Acting

Acting is pretty strong across the board. In a confined feature like this one that relies on the believability of the tension between its characters, acting is incredibly important and Boots on the Ground largely succeeds. From the get-go, each character seems to represent a certain character type, with Ollie and Pawlo vying for leadership and Swiftee turning into the paranoid guy who winds up making things ten times worse for everyone.

Ian Viago and Tom Ainsley play the antagonistic-yet-somehow-friendly relationship between Ollie and Pawlo, respectively, very well. Both the tension and camaraderie completely come through, and doing both of those things at once is incredibly hard to pull off for any actor. Ryan McParland, as Swiftee, is playing a character trope, but he’s nailing it. He completely sells this person who is overtaken by fear to such a point that he’s well beyond the capacity for making a rational decision.

But there’s something great that happens as the film goes on. Actors who don’t leave much of an impression in the first half of the movie wind up dominating it in the second half. Conway and Mo have very little to do during the early scenes, but when things ramp-up, characters that one would almost expect to be cannon fodder actually become the most complex and engaging.

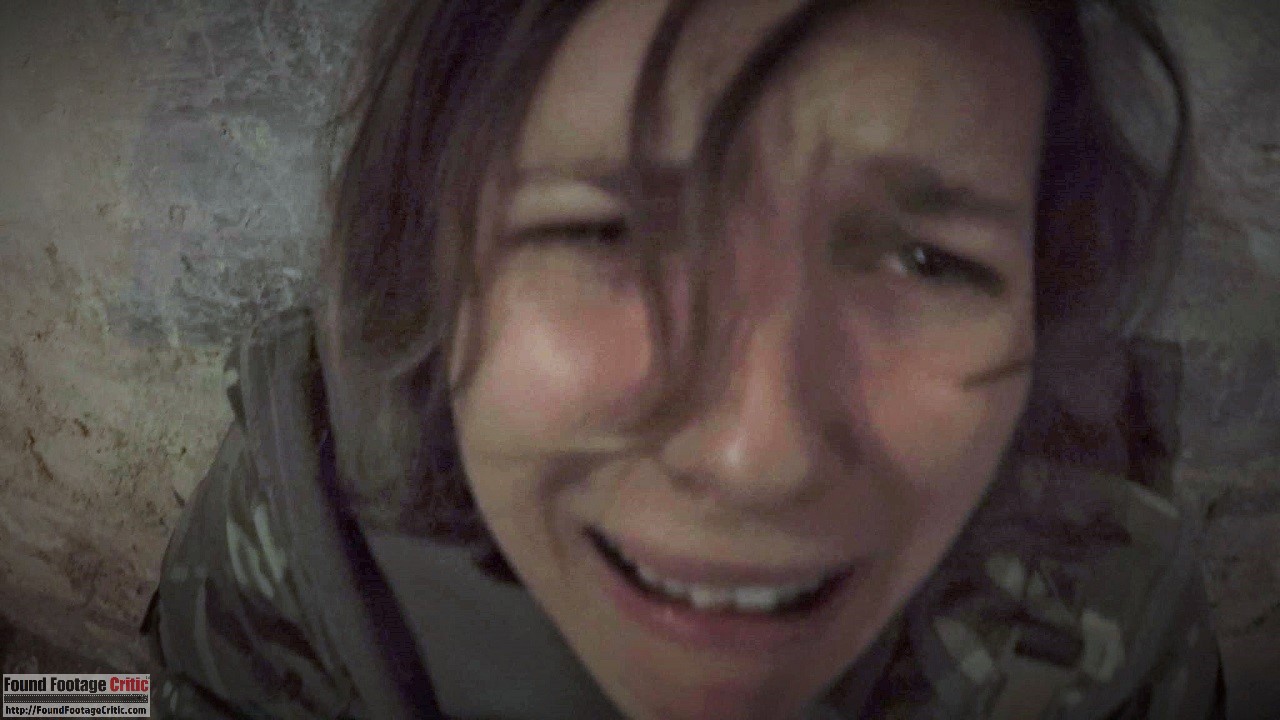

Mo, who has virtually no voice early on, winds up being the voice of reason and the most level head of the bunch. Conway is the only one with an established family and something to lose, and those stakes only give weight to how believably terrified she is as the horror amps up. Both Valmike Rampersad and Sally Day sell those characters well, especially as the film goes on and the characters are given more and more to do. It’s a small cast and any weak link would immediately stand out, but Boots on the Ground thankfully doesn’t have that problem.

Plot

The plot of Boots on the Ground isn’t anything new or revolutionary, but Melville makes the most of it. What is relatively unique to found footage is the ending of the film (which we discuss in a spoiler paragraph below). Ultimately, this is a film that’s less about the situation and more about how the characters react to it. That’s what makes it interesting to watch, even if those characters do get repetitive at times. It’s tense and it keeps the viewer guessing and that’s what a supernaturally charged movie like this is designed to do. There are several instances meant to make you question what’s real and what isn’t. Some of them are played to great effect.

When not too dependent on visual FX, there are scares that are set up extremely well. There’s a moment between Conway and Swiftee that’s legitimately horrifying. Even though the plot becomes predictable, those moments of genuine intensity make it an easy watch. Many of the larger issues with plot and pacing seem to stem from lingering on a moment or a scare for a little too long. This stands out in particular at the end, as there’s a terrific, jaw-on-the-floor ending that comes two minutes before the movie actually wraps up, thus significantly lessening its impact.

Now to get into spoilers. The ending in question is a great twist that plays out almost without drawing too much attention to itself. We simply find the characters back at the fortress only to reveal that they are the British troops they followed in there to begin with. It’s a fantastic reveal. These characters are dead. They’ve been dead the whole time. Had that moment been the ending, it would have been fantastic, but when it goes on for a few extra minutes, it lessens the impact. The idea itself is great, though. Voodoo (2017) is another recent movie to use the same general conceit. It would be really neat to see more found footage efforts play around with these ideas in the future, as they offer a totally different take on the format.

Overall, a few errors and inconsistencies, even some of the bigger ones, aren’t enough to truly sour what is generally a suspenseful, enjoyable watch.